If money is the lifeblood of an economy, then banking is the heart that keeps that blood pumping.

Banks in their most basic form are simply financial intermediaries that help people who have money (depositors) find people who need money (borrowers). A world without banks is inefficient. It’s also risky. It places the burden of handling transactions, securing money, and facilitating investments in the hands of everyday people who in most cases aren’t equipped to take proper care.

“If you are going to function in society, as an individual, a mom-and-pop business, or a billion-dollar corporation, you need one or more of the following: a bank account, a business loan, a car loan, or a mortgage, and with every bank account, business loan, car loan or mortgage, comes fees charged by the bank for the myriad services it provides.”

― Warren Buffett

Banking is inherently a fragile business. In banking, a single event can play a significant negative role — Like the bank makes profits for years, then loses all and more it ever made in a single episode.

It’s the consistency, not the amplitude, of earnings that drive long-term value in banking. The first rule of compounding, Charlie Munger once said, is to never interrupt it unnecessarily. This is especially true in banking, where losses can snowball into acute shareholder dilution.

The financial sector appears glamorous, but it is fundamentally very fragile. Therefore, it is crucial that a firm has the simplicity and humility to say that this is a very difficult real-life business. The business of money is truly "fragile, handle with care".

— Uday Kotak

This is due to leverage—leverage is a double-edged sword. To many people, the biggest risk in the banking industry is leverage - banks are inherently levered entities. Leverage is simply the use of borrowed funds (which for a bank includes deposits), as opposed to equity, to purchase or otherwise acquire assets and run operations. In and of itself, leverage isn’t good or bad, it’s simply a tool. Leverage is a magnifier.

One thing that makes banks different from traditional companies from a leverage standpoint is that banks are experts in managing risk. This is what they do (or are supposed to do anyway) all day long. For an industrial company borrowing to finance equipment, the sky is the limit when it comes to the potential return on their investment. Banks, however, lend money with known return characteristics. A bank’s risk department is responsible for ensuring that the bank doesn’t concentrate too many loans in a given sector. The underwriting department’s mandate is to attempt to write loans that will not lose value. Banks aspire to perfect underwriting records, even though that’s impossible. In addition, a bank can manage its deposit cost to better match up with its lending portfolio risk.

“Risk management lies at the core of what distinguishes financial institutions. One of the things fintechs are very good at is understanding customer convenience. But there is a balance between customer convenience and the safety of their money. This is a very important distinction — one that we as bankers normally learn the hard way. As a leveraged institution, the bulk of our money is other people’s money, and the net equity ratios of banks are obviously much higher than those of any other form of company…

Banks focus on managing risk because they have very small capital and a large amount of leverage. Fintechs are a while away from grasping the consequences of getting it wrong with leverage or customer security and losing money because of it. This is where I think the roles of fintechs and banks are going to be more complementary. Banks, meanwhile, can learn a lot from fintechs about being customer-friendly.”

— Uday Kotak

The biggest actual risk to a bank is the same risk that exists for any company - operational risk. This is the risk that management makes bad decisions. Perhaps they grow too quickly or in the wrong direction, hire the wrong people, make bad loans or other investments, and so on. It takes a master swordsman to balance opposing forces to triumph at the battleground of banking. Uday Kotak is one such master swordsman — A banker among bank “executives”. He exhibits the even temperament that’s needed to steer highly leveraged institutions through the unforgiving vicissitudes of the credit cycle.

Born in Mumbai into a large joint family of Kutchi Gujarati traders, Uday Kotak had a keen entrepreneurial spirit, inclined more towards finance than his family’s commodities trading business. After an MBA from the Jamnalal Bajaj Institute of Management Studies, Mr. Kotak thought of a financial consultancy firm, but a keen eye for opportunity drew him towards discounting bills of large corporates.

The First Taste Of Spread

In the 80s, Uday Phadke, one of Uday Kotak’s friends from JBIMS joined a Tata company, Nelco. Nelco was in the business of radios and electronics and always found itself tight on working capital. As its suppliers had to be paid 90 days later, Nelco used to borrow money for 90 days from banks at 17% through bill discounting, a rate mandated by RBI back then. Also, under the Credit Authorization Scheme (CAS), large companies like Nelco had a cap on the money they could raise from banks. The cap, at the time, was Rs. 5 crore. So, suppliers used to be in distress due to delays in payments.

Uday Phadke made Mr. Kotak a proposition, He said, ‘If you have some affluent friends, Nelco will accept a bill of exchange. You arrange payment for the supplier. And at the end of 90 days, Nelco will pay back the money. It is a Tata company, after all.’

‘At what rate of interest?’ Uday Kotak asked.

‘At 17%’ Uday Phadke responded.

In those days, bank deposit rates (fixed deposits) were 6% and lending rates were 17%, as fixed by India’s central bank. The banks were making a large spread, and there was money to be made by anybody who could enter and find a way of reducing this spread. This is where Uday Kotak sensed, “Your margin is my opportunity.”

Uday Kotak spoke with a few friends and family. He offered them a 12% return if they were willing to take the “Tata” risk—The name Tata was synonymous with security. He raised small amounts from each contact, ranging between Rs. 50,000 and Rs. 1,00,000. And instead of lending Nelco money at 17%, Uday Kotak said to Uday Phadke. ‘You give me more business. I shall make the lending rate 16%.’ Earning a spread of 4%.

The fact remains that Mr. Kotak got his first business with zero capital invested. And that is how Mr. Kotak got into bill discounting—the buying and selling of paper.

“We bought it at 16%, and like a holder in due course, we endorse it. I would give physical hundis to investors, with invoices, challans, etc. As a bill of exchange is a negotiable instrument, we used to buy the bills, write the cheque, re-discount them and keep the spread. The banks were making 11%; we were making 5%. Due to the complexities of the interest rate system and differential spread between the deposit and lending rates, where banks were working with the spread between 6% and 17%, we could intermediate and create a market. That is how we started and soon the business grew…

Later all the foreign banks came - European Asian Bank and others. None of them had a deposit base here. But they were ready to take credit risk, so they would do what was known as co-acceptance. You also had another set of foreign banks and Indian banks who had surplus money like Standard Chartered, American Express, and some of the Indian banks, in which case, it became an inter-bank risk. If a Nelco bill was co-accepted by a European Asian Bank, you could do an inter-bank risk transaction. We then moved beyond individuals - to buy bills and refinance them from Indian banks. That’s how the whole bill discounting saga played out…

We made significant profits through bill discounting because the market was imperfect and there was no concept of the private sector in financial services.”

— Uday Kotak

Symbol Of Trust

In banking or finance, trust is the only thing you have to sell. Mr. Kotak had decided quite early that he would not refrain from putting his reputation on the line. This resolve became stronger when he read numerous books on top financial institutions like JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley carrying their family names. He, too, decided to put his name, front, and center. Today, Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) is the only Indian private sector lender which retains the family names of its promoters.

Like Nelco, Mahindra Ugine Steel was also a Kotak client. It was through this relationship that a game-changing event occurred in 1985, when Uday Kotak first met Anand Mahindra, now chairman and managing director of the Mahindra Group.

Steel was always in need of working capital. When they met, Mr. Kotak told Anand Mahindra, ‘We will raise money for you through bill discounting in 72 hours.’ In those days, 72 hours was quick.

Anand Mahindra, just 30 at the time, was impressed with the young Uday Kotak:

“When we met, the mini steel business was in recession. I remember asking him why he was willing to lend to us given the industry’s fragility. He promptly replied that his credit evaluation was based on the promoter’s reputation and record,” “I vividly remember being very impressed with his [Kotak’s] maturity and my gut instinct told me this young man was going to make an impact on whatever he chose to do. So rather impetuously I told him that if he ever decided to expand his firm and get into the leasing business—for which the government had recently liberalized licensing—I would be pleased to back him.”

— Anand Mahindra

Anand Mahindra subsequently invested Rs. 4 lakhs in Mr. Kotak’s venture in 1986. Apart from money, Mr. Kotak asked Mahindra to be able to associate the Mahindra name alongside his own. Mr. Kotak explained to Mahindra,

We are in the business of reputation. Names matter. Let’s put our names into the company. Let’s show people that we care enough about this business to put our names on it.

And thus, Kotak Mahindra Finance Ltd. (KMFL) started operating as an NBFC in April 1986. With an initial capital of Rs. 30 lakhs.

Taking On The Mighty Citi

In 1989, another major opportunity presented itself to Mr. Kotak, when Citibank entered the car financing business in India. Citi offered customers car loans at a flat 13% hire-purchase rate of interest, which remained the same even though the loan balance lowered, thereby taking the bank’s internal rate of return to as much as 36%. That was the kind of spread in the car loan business. Foreseeing the opportunity, KMFL immediately entered the business of car financing. As an NBFC, it borrowed from banks to lend to customers against their vehicles as security.

There was no way we could compete against Citibank, but Citi had one constraint. They could lend against cars only when the vehicles were available and cars were in short supply. Having a ready car to sell was a differentiating factor.

Uday Kotak recalls,

We came up with an interesting solution. Maruti was making the most popular car then, with a six-month waiting period for delivery. So, we started the concept of booking cars in bulk, so that when the customer wanted, we could provide instant delivery. We could pre-book 5,000 to 10,000 cars in our own name, effectively like a dealer would, but with the understanding that when the car was delivered, ownership would be moved to the customer’s name. Thus, we were able to give our customers instant delivery. However, in those days, there was a high premium on the cars, We decided not to charge the premium, but customers who wanted the car from us on instant delivery terms had to get the car financed from us. That is where the spread was and we were able to compete with Citi. The finance terms and interest rate were same as Citibank—13%, It worked and became a good business for us.

Turning Into A Bank

On 2 January 2001, Dr. Bimal Jalan, then announced the opening up of the Indian banking sector to private sector banks by giving out new bank licenses and releasing the guidelines for new private sector banks.

The decision to transform itself from an NBFC to a commercial bank was the result of long deliberations among the core Kotak Mahindra team. Mr. Kotak felt that if they have to be a sound, stable, strong financial institution in India serving customers, they must have a banking platform.

“At that point, nobody was interested in banking. If we had to be meaningful in India, we had to have a full customer view.”

— Uday Kotak

And thus, Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB), a new private sector bank, the first NBFC to be converted into a commercial bank, was born in February 2003.

As a new bank among established players like HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank, KMB needed to position itself differently from the other banking companies.

Mr. Kotak clarifies the thought that went into the question:

Our platform is based on two simple principles. One is convenience and the other is solutions. We offer convenience by telling our customers they can use any bank’s ATM and we will pick up the tab by providing a pretty significant home banking facility, where we pick up cheques or cash from a customer’s home. We have a small customer base and we bring a differentiation; the larger banks cannot compete because they cannot offer the same facility to millions of customers.

The second platform is - solutions. How do we differentiate ourselves as ‘Bank No. 110’? I don’t remember the exact number, but we were pretty low down. We decided to start a bank that would provide high-quality differentiated advice that was concisely caught in ‘Think Investments, Think Kotak.’ Our entire branding is based on that - it is the origin of ‘Think Investments, Think Kotak’. In India, most banks don’t talk about investments, capital markets, etc. We offer solutions and advice.

Propelling Into The Big League

Acquisitions have been hard to come by in the banking sector because good assets are never available at a reasonable price. Kotak Mahindra’s all-stock acquisition of Bengaluru- headquartered ING Vysya Bank in November 2014 was a strategic move that came at a reasonable price.

The deal not just brought size, but also reach in terms of a complementary branch network. The merger helped Kotak double its branches and expand its network pan-India, with a deeper focus on the south. The bank garnered a total of 64,600 crores in assets and 44,600 crores in deposits, making it the fourth-largest private sector bank in the country with assets totaling 1,98,000 crores and deposits amounting to 1,12,000 crores at the time of the merger.

The deal helped KMB leverage ING’s digital banking strength, as ING was among the top two or three consumer banks in Germany with zero branch presence. It helped KMB ramp up its branch presence in South India, in a scenario where 46% of KMB’s branches were in West India only. The bank was also able to diversify its loan book beyond its own retail loan business, as ING’s strength was its small and medium enterprises (SME) clientele. With ING Vysya nearing the foreign shareholding cap of 74%, the merger also yielded more liquidity and significant headroom for foreign money, as the foreign shareholding was 47%. The deal also helped Mr. Kotak reduce the promoter’s stake in KMB, in line with the roadmap given by the RBI, and move towards the prescribed stake of 30%.

Business of Exclusion

Banking can be thought of as a business of exclusion. Banks are more or less market takers on deposit and lending rates. That is, they generally must do what the market as a whole dictates as it relates to rates on loans and deposits. A bank might be able to make a few extra points at the margin, but deposit-taking and lending are in most cases commodity businesses that are incredibly competitive.

Because banks are taking deposits and making loans at the market rate, the levers they have to control their performance are the types and quality of the loans they make and their expenses. Banking is a business of exclusion because bankers need to be able to walk away from questionable loans, whether as a result of the quality of the loan itself or the pricing. In an environment where people need money, it is prudent to pass on most deals and only extend loans to the best borrowers at the best possible prices.

Interestingly, if a bank pays the average rate on deposits, earns the average rate on loans, avoids bad lending, and has average expenses, it isn't an average bank, but an above-average bank. As Warren Buffet says, “Banking is very good business if you don’t do anything dumb.”

With little differentiation in finished products (loans and services) and no aspirational value attached to these products, low raw material cost (as measured by the cost of funds) and superior execution are the only two key competitive advantages for a bank. Moreover, a hugely leveraged balance sheet (10x leverage is normal for banks) means that below-par credit selection usually has a disproportionately large adverse impact on the bank’s profitability.

The Road To Power (Less Risk On The Asset Side) In Banking Is Paved With Low-Cost Liabilities (CASA)

Customers view deposits as a place to safely store their money and perhaps get interest payments, whereas bankers view deposits as a funding source, the fuel for their lending engine. Customer deposits can be a huge source of strength for a bank. A bank that can successfully acquire cheap and “sticky” deposits (i.e. deposits from customers who expect little in interest that are unlikely to walk quickly out the door for a little extra interest) can gain an advantage over competitors. Banks without strong deposit networks struggle to fund their daily operations.

The move by the Reserve Bank of India to de-regularise interest rates on savings accounts in 2011 helped KMB build its CASA franchise, which has significantly contributed to lowering KMB’s cost of funds.

Though nobody saw an opportunity, Kotak moved quickly and leveraged this opportunity by increasing its savings bank interest rates to 6% for balances above 1 lakh and 5.5% for others – a move that translated into significant growth in savings accounts. Within 2 years of RBI’s interest rate deregulation, Kotak more than doubled its savings account book from 3,330 crores as of 31st March 2011 to 7,268 crores as of 31st March 2013, posting a CAGR of 48%.

KMB launched a campaign ‘6 is bigger than 4’ hitting at the 4 percent rate that almost all banks were offering at that time. While the savings account book of Kotak was at 3,331 crores in the year ended March 2011, it leapfrogged to I,69,313 crores in the year ended March 2021.

Initially, KMB was losing money on the retail deposits, but this customer acquisition cost was necessary to take short-term pain for long-term gain. Kotak has the ‘capacity to suffer’. These retail deposits are extremely “sticky” in nature, “Once you onboard a deposit customer, the relationship is practically lifelong. So, you first need to attract deposit customers before you can start offering products and services to them,” says Dipak Gupta.

Stability is critical, and that comes from savings accounts. Not only is the cost of funds lower on these accounts, they also allow the bank to cross-sell financial products to a larger base of customers. For example, in the unsecured credit card business, 90% of the bank’s incremental signups come from existing customers.

Recently, Uday Kotak realized every banker’s dream — “We have dropped rates, at the same time we have kept the customer franchise.”

A bank’s deposits provide a low-cost source of funding and are a crucial asset that should be cultivated and nurtured. Too many banks view their deposits as a cost center, but deposits aren’t the only expenses for a bank. A bank also has expenses related to acquiring and supporting its deposit base.

“We consider the customer franchise as a key part of our decision. We are not going to give away our customer franchise and the savings deposit growth strategy which we have had, while obviously being conscious of the commercials of what we are doing. Therefore, it's a very careful balance we are doing between those, and ensuring that the franchise of sustainable and low cost deposits and the competitive advantage we have, we keep on driving home while reducing the cost of funds for the Bank.”

— Uday Kotak

KMB’s CASA ratio has increased from 32.2% at the end of March 2012 to 60.7% at the end of March 2022. While CASA ratio for HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, and Axis Bank stands at 46%, 41%, and 45% as of March 2022. This provides a significant competitive edge, as they are able to leverage their low cost of funds to lend more aggressively and open up further opportunities to acquire high-quality customers.

Now, you must be wondering that despite paying more interest on deposits to customers as compared to peers, how come Kotak has the lowest cost of funds. This is because the incremental deposits were growing at a very fast pace and became a higher proportion of the overall funds. So, despite paying higher interest on SA, Kotak managed to have a lower cost of funds by having the proportion of CASA higher than its peers. This made Kotak have the proportion of least preferred deposits which are term deposits lower than compared to its peers.

CASA plus term deposits below 5 crores account for 91% of the total deposits for KMB.

When everything can be processed online a bank’s branches have lost their value as a touchpoint for customers and have become an expensive line item on financial statements. It doesn’t make sense to employ people to serve customers in a building that customers never frequent. “Today, every customer has the branch on their mobile. The mobile is the biggest branch. ” says Dipak Gupta.

What we look out for is customers and capabilities, not physical branches. When I say I have 1600 branches, I think it would be a liability if I had 10,000 branches. And that's very clear because I think the digital and technology change is going to make the density of branch network requirements… more even for current account customers, for savings account customers… 94% of the transactions have moved outside the branches…

— Uday Kotak

Fundamental to Kotak’s strategy going forward is a combination of conventional branch banking and digital banking.

It took Kotak Mahindra Bank eight years to acquire its first million customers. The next 2 million came in just four years, thanks to the 6 percent savings account offer it rolled out in October 2011 when the Reserve Bank of India deregulated savings interest rates. If 6 percent gave Kotak its ‘aha’ moment, 811 gave Kotak its ‘gaga’ moment. ‘811’ — a banking app that allowed customers to open accounts with zero balance and complete all KYC formalities on their smartphone in just under 10 minutes. Kotak was the first bank in India to integrate the Aadhaar-based OTP authentication process for account opening on mobile. Only Aadhaar and PAN numbers are required to open and operate 811.

This app was inspired by the date on which Prime Minister Narendra Modi had announced demonetization—8 November or 8/11. The goal was to try and double the customer in 18 months and was in fact KMB’s response to the disruption in banking.

In January 2020, when the RBI amended Know Your Customer (KYC) norms and introduced the video-based KYC option to onboard customers, KMB was the first bank to integrate the video KYC process in the account opening journey.

The launch of 811, India’s first downloadable digital banking ecosystem with biometric-led KYC verification, has resulted in a paperless, real-time banking experience for customers, reducing the turnaround time for opening a bank account from a few days to a few minutes, has reduced the cost of customer acquisition and has increased the productivity of field force. This new product has significantly reduced the cost of customer acquisition, compared to its regular accounts, by almost 80-90%. Even more, servicing these accounts costs next to nothing.

Asset quality is paramount.

Asset quality is paramount. As an outsider, we don’t have access to know or understand the details of a bank’s troubled assets. What we do know is the level of troubled assets in relation to their capital and the trend of their troubled assets. Use history as a guide.

KMB has managed to maintain strong control over asset quality on a multi-year basis. The bank’s gross non-performing assets (NPA) largely remained between 2% and 3% over FY15-FY19 and moved up to 3.56% at the peak in 1QFY22 during the pandemic. The bank has further demonstrated its control of asset quality with GNPAs at 2.34% in 4QFY22, despite the ongoing pandemic. Similarly, the credit costs have remained in the sub 1% range on an annual basis even during events such as demonetization and implementation of the Goods and Services Tax and The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act. However, the bank’s credit costs surged in a few quarters during the past two years due to the creation of COVID-19-related provisions in addition to the provisioning requirement during the pandemic. However, while KMB has written back 452 crores from the COVID-19 provision buffers in 4QFY22 with the impact of subsequent waves of the pandemic becoming less impactful, it still carries 547 crores as additional COVID-19 provisions.

A non-performing asset is a loan or an advance where the borrower has stopped making required payments for 90 days or more. It’s important to note that designating a loan as non-performing doesn’t mean that it’s worthless.

When a loan becomes non-performing the bank begins the process of maximizing its recovery either via foreclosure of the property, repossession or through filing an involuntary petition for bankruptcy against the borrower.

Think of past-due loans and NPAs as an early warning system for future potential problems. If a borrower starts to miss payments or make late payments for extended periods of time it is likely, or possible in any case, that they are experiencing some financial distress.

What makes Mr. Kotak the banker that he is that, RBI asks to wait for 90 days to declare an account NPA, Mr. Kotak said that “even if it is not 90 days, in our assessment if there is an inherent weakness in the account then we will go ahead & classify it as NPA.”

“Where we have questions on the viability of the business, we have taken a bolder call, let this flow-through NPA rather than give moratorium which is kicking the can down the road.”

— Uday Kotak

Net NPA is the amount resulting from the sum of the defaulted loans after deducting provisions for uncertain and unpaid debts. As of 31st March 2022, Kotak’s net NPA stands at 0.64%.

The provision for loan losses is a contra account found on the balance sheet. That is, it’s simply a reserve for expected or anticipated losses on outstanding loans. Periodically, a bank will review their loan book and analyze whether they expect (based on certain criteria) to receive the contracted principal and interest on each loan. To the extent they determine a loss might be suffered, they are required to reserve funds to cover that loss. If and when losses are incurred, the loan loss reserve account is reduced.

Kotak aggressively provisioned in the early phase of the Covid crisis.

A well intended measure of smoothening cash flows through restructuring runs the risk of becoming a tool for 'ever greening'.

We don’t like restructuring as a philosophy, so we’ve always been very conscious and conservative about doing restructuring. We would rather take it, and take the pain through P&L and get our recoveries… First on let me just give you again something which is on philosophy which is important. If we have to restructure a loan, as long as we are not going to lose our money, we are comfortable making an NPA and then restructuring as a philosophy. And therefore, if you look at our restructured standard loan it is the lowest in banking. And that is coming again out of a view that much rather restructure after taking it through the NPLs if we have to. And of course, it is not that we don’t restructure just for the heck of it. Because when you take a loan to an NPA, your provisioning is much higher than a restructuring, number one. Number two is in a restructuring you continue to accrue interest. In an NPA, you stop accruing interest as well as reverse the accrued interest. So both these from a revenue and P&L point of view are significantly different from a standard restructured loan but we are happier to do that because at least we know what are the things we really need to focus on and get on with, trying to get fair value of that asset.

— Uday Kotak

After the Covid crisis, Kotak has a minimal restructured book. The standard restructured book, whether it is through COVID-1, COVID-2, or MSME resolution framework all put together, is 0.54% of its overall book.

Examining a bank’s assets for future risk is worthless if the bank is currently on shaky footing. And as we can see, Kotak is on a strong footing.

A bank's troubled assets show what’s happening now, the bank’s loan portfolio holds the key to what could happen in the future.

When looking at a loan portfolio, one should try to envision the types of ways the portfolio could cause the bank issues in the future.

Future credit risk at a bank is determined in part by looking at the existing trends related to the loan portfolio and extrapolating them into the near-term future. It should be pointed out that extrapolations far into the future don’t hold much predictive value, but in the near term, outside of exceptional circumstances, current trends tend to continue until they’re forced to change.

Ultimately, a bank’s lending mix in terms of size, yield, and industry will determine its profitability and related risk profile. Lending is a balancing act between loans that are potentially riskier but yield more, versus loans that are perceived or deemed to be safer, but yield less. A bank also needs to balance the size of loans and borrower mix.

The types of loans, the duration of those loans, the lending mix, as well as the historical performance, tell a story about a bank’s management and the quality of its lending. For Kotak, lending is rooted in the belief of being a custodian of depositors’ money and providing returns for years.

Kotak has always been focused on building a healthy and profitable business. It has been particularly focused on ensuring the right risk-return metrics. Pricing models such as Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital (RaRoC) measurements have got ingrained in the system.

“It’s not that we’re scared of taking risks. When you look at our stressed assets portfolio, bought from other banks, you might say we are the highest risk-takers in the industry. But we are willing to take risks after understanding them and believe the pricing must justify the risk.”

— Dipak Gupta

When looking at a bank’s loan portfolio, ask yourself the question, “Is this sustainable?” Is the bank’s lending mixture sustainable in both good times and bad times?

Kotak has proven time and again that its book is sustainable in both good and bad times. It has a well-diversified, sustainable asset book with a balanced mix of Wholesale (Corporates and SMEs), Commercial (Commercial Vehicles, Construction Equipment, Tractor, Agriculture), Secured Retail (Home Loan, LAP), and Unsecured Retail (Consumer Durable, Credit Cards, Personal Loan) with few drips and drabs of other lendings.

The crux of banking is watching what others are doing and then not doing it yourself.

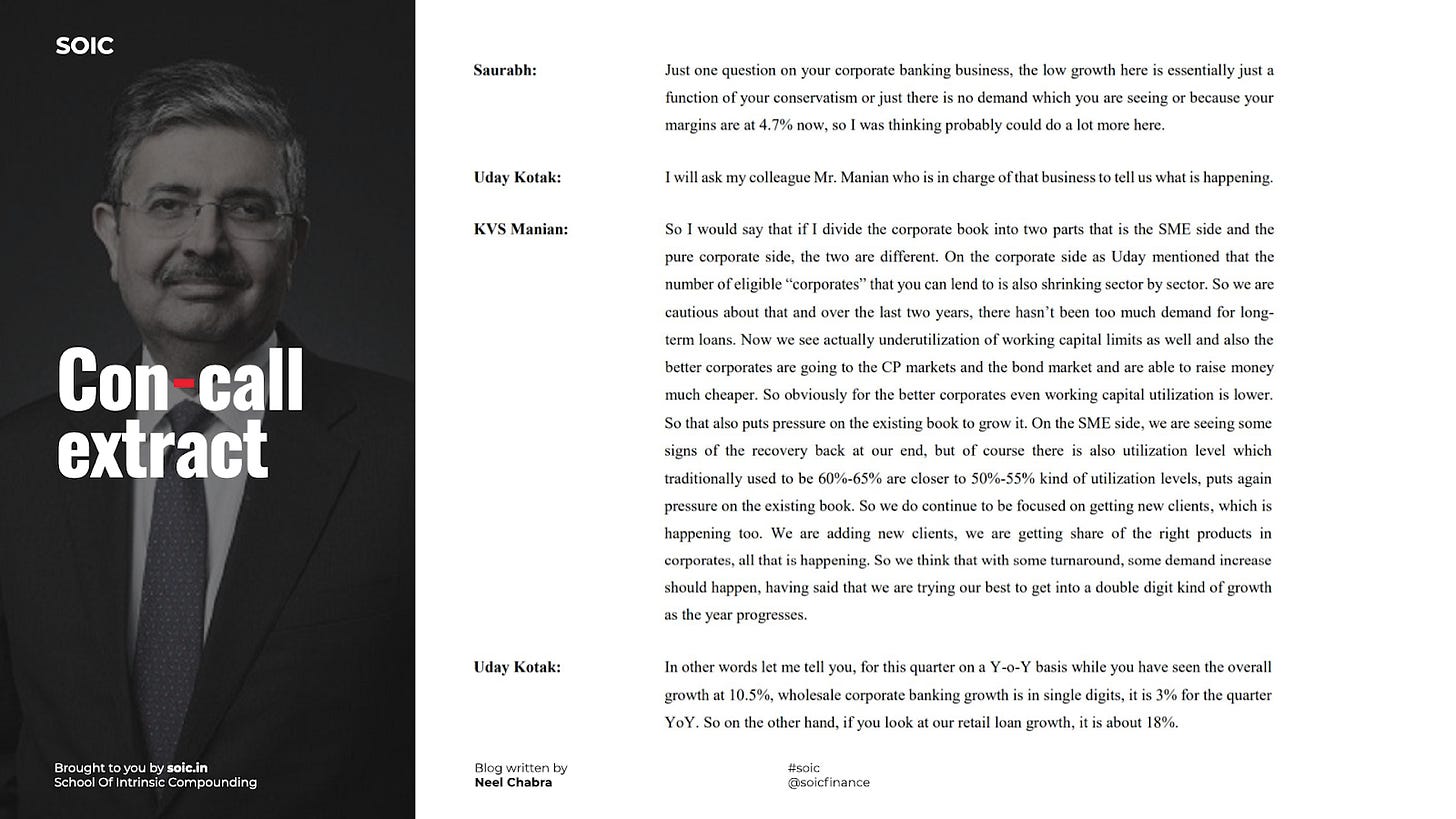

With the Indian economy booming during the 2000s, corporate banking grew rapidly as companies went into an expansionary mode. Several fledgling private sector banks such as ICICI Bank and Axis Bank were gaining heft lending to corporates during the bullish years till 2008, but Kotak Bank displayed little aggression. Unlike others, Kotak adopted a prudent and cautious approach, targeting only high-rated customers and sectors. It avoided riskier longer-term project finance in favor of shorter duration loans and secured working capital loans, given its conviction of taking only lenders’ risk and not equity-type risks for lending returns. This allowed it to build scale in its corporate banking business in a healthy manner.

Uday Kotak did not succumb to temptation even as peer banks, especially foreign ones, were aggressively offering derivatives products to corporate clients and taking away business. When the cycle turned and banks started going slow on corporate lending given stress in their books, Kotak sensed an opportunity and started targeting market share to ramp up its corporate book. Over the past few years, corporate assets have consistently grown by over 20% and their proportion to the overall advances has increased to 39%. Kotak continues to differentiate itself in its strong understanding of risk, helping it to deliver healthy and profitable growth. The use of Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital models has assisted pricing optimization and helped to better judge the risk-return metrics. Risk-Weighted Assets as a percentage of total assets have consistently declined, and the book enjoys industry-low NPAs even at the time of COVID.

From 2010-to 2012, Kotak had shied away from infrastructure financing, even as other banks and financial institutions had dived in. “These projects promised higher yields, but it was a space we did not understand and has been known to often cause asset-liability mismatches,” explains Jaimin Bhatt. For those who did lend to the sector, time and cost overruns showed up in a few years, resulting in huge non-performing assets (NPAs) that they are still struggling to recover from.

Over the past year, instead of direct lending, Kotak saw a greater demand for credit substitutes, a type of lending wherein the bank subscribes to corporate bonds or non-convertible debentures of top-rated corporates. “As an alternative to lending as loans, we have frequently invested in bonds of companies. In terms of risk management, it is better when you have bonds as you can manage exposures by selling them any time you want, unlike loans,” says KVS Manian. As of March 2022, the credit substitutes portfolio stood at ₹21,227 crores.

The Bank’s maxim that ‘return of capital is more important than ‘return on capital’ has manifested itself many times in its history, and one such example is its Commercial Vehicle/Construction Equipment (CV/CE) loan book. When the CV/CE financing business was going very strong, the Bank foresaw the danger of over-heating in the market and that the industry was prone to overcapacity. Kotak had its ears to the ground and chose to be contrarian by consciously reducing its exposure to CV/CE financing from December 2012. As a result, Kotak’s CV/CE book came down to ~ 5,000 crores in December 2014 from its high of ~ 8,000 crores in September 2012. During that period, the Bank reduced its monthly disbursement by 80% and largely catered to its existing good customers. The CV/ CE book came down, but there was no shutting down of branches, and Kotak chose to take the operating expenditure pain rather than capital pain – a strategy that proved to be beneficial amid the peaking NPAs and defaults in the industry. By September 2015, however, on regaining comfort in the segment, the Bank again started increasing disbursements, bringing its book back to 8,000 crores in June 2016 and is standing at 22,490 crores as of March 2022.

Over the last 2 years, Kotak has barely grown its loan book. Uday Kotak was the first one to warn about stress in unsecured retail. He now says: “ We have undertaken a mindset shift to make retail and commercial lending our focus, in addition to the corporate and deposit franchise. For example, we are leveraging our low cost of funds to offer a competitive interest rate on home loans. Home loans give us an opportunity to build a longer-term relationships with customers. And we will get bolder in unsecured retail finance too, for which we’ve kept our powder dry over the last two years.”

For home loans, we think home loans is one of the most sticky products in a customer journey. And the ability to cross-sell a variety of products to a home loan customer is also a significant opportunity. A home loan customer who has got a core mortgage is a much safer customer to add a credit card or a personal loan, a home loan customer who has an engaging bank account, that again gives us a deeper engaging relationship with that customer. So we look, we are getting significantly more focused on customer engagement and customer returns, in addition to making sure that the product makes economic sense.

— Uday Kotak

“While distribution width and low-cost funds are important in the mortgages business, in today’s digital world, how you leverage technology to scale business and think differently matters. Also, the home loan market is a deep and wide market with sub-segments between ₹10 lakh and ₹10 crores. Within unsecured retail, the bank is building its credit card business by leveraging its upgraded tech platform. We had one of our best quarters with the acquisition of 3.9 lakh credit cards in Q3. The bulk of the sourcing has come from existing customers.”

– Shanti Ekambaram

Kotak Mahindra Bank has now “pressed the accelerator” on unsecured products and is confident that credit cards as a product will continue to stay, although form factors may change due to technology developments and changes in consumer behaviour.

We would like to replicate our home loan strategy where we have dramatically increased market share in recent days and will gradually achieve Kona Kona Kotak Credit Card (Kotak card in every corner) in days to come.

Going forward, Kotak Mahindra Bank also plans to invest more in Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) given the potential in that area.

— Ambuj Chandna

Net interest income is the difference between the amount of interest income the bank receives and the amount of interest expense the bank pays or incurs. Perhaps the most popular way of calculating this measure of profitability is by looking at a bank’s net interest margin (NIM) which is the difference between the income earned on interest-earning assets (i.e. loans) and interest expense incurred on liabilities (i.e. deposits and borrowed funds) to carry those assets, expressed as a yield.

NIMs shouldn’t be looked at in isolation. You have to look at NIMs along with the operating cost. While retail loans have higher NIMs, the operating cost is also high. And while on the corporate side, NIMs are less, the operating cost is relatively low.

Kotak had a NIM of 4.78% as of 31st March 2022. This is despite having a lot of assets in treasuries during the year, which yields less.

Over the past 8-9 years, Kotak has focused on getting its liability engine in place. Going ahead, they will focus on getting its assets' engine to start firing.

A bank’s capital is best viewed in light of its loans and asset quality. It’s when those contexts are understood that a capital ratio makes sense.

Banks with too little capital should be given extra time for investigation, but banks with too much capital should as well. A bank that has too much capital has an inefficient and lazy balance sheet and isn’t maximizing its earnings. This is because too much cash is sitting on the sidelines and isn’t being lent out and used to make a profit. A bank’s purpose is to take insured deposits and invest those deposits into loans, not take deposits and invest them in a bond portfolio or simply hold them as cash.

A bank should have a pyramid structure to their assets, with their loans forming the base and being the largest item. The next layer in the pyramid is investment securities. The amount of securities should be less than the loans, but more than cash on hand. Finally, at the top of the pyramid is cash. When a bank doesn’t have a pyramid with its assets, they are conducting business inefficiently.

Kotak has a Capital Adequacy of 24%, among the highest in the Indian banking industry, and has a pyramid with their advances at 2,71,254 crores, investments at 10,05,80 crores, and 42,924 crores in cash as of 31st March 2022.

An easy litmus test for any bank is how it performed through the crisis.

Well-run banks embody the idea of antifragility. They underperform by a little in good times but outperform by a lot when times get tough.

Kotak has proven time and again that it is antifragile among fragile.

By the late 1990s, NBFCs were the flavor of the season and there were over 4,000-odd players spread across the country. But Uday Kotak was able to see the big picture quite early.

The nineties saw non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) mushrooming across the country. However, the Southeast Asian crisis of 1997-98 became a major testing point. Before the crisis, there were 4,000 NBFCs in India. Within the next couple of years, 99 percent went under. We were one among the two dozen-odd that survived, learning valuable lessons along the way.

We were getting very uncomfortable with the macro scene then — rates were high, companies were struggling to repay and the economy was slowing down. So we started to bring down our book dramatically. Only 1% of NBFCs survived that downturn and we were lucky to be one of those.

— Uday Kotak

Just a year before Asian Crisis, Uday Kotak saw the pain and pulled back to shrink the balance sheet from 1,800 crores to 1,000 crores. He could see that the financial sector was likely to go into serious defaults. So, he pruned his balance sheet by design. Thus keeping non-performing assets (NPAs) in check. Between 1997 and 1999, net NPAs were down to 3% of total assets from the earlier 5.51%. More importantly, it had healthy capital adequacy of 25% as of March 31, 1999.

Faced with the Asian crisis, several companies in India ended up defaulting, triggering a liquidity crisis for NBFCs, including some of the established ones. Over 3,000 NBFCs were impacted, and many collapsed. Kotak’s extreme prudence and conservatism, as an NBFC back then, not only helped it sail through the crisis but placed it in the enviable position of having other NBFCs approach it for their recoveries. Kotak saw this as an opportunity to pioneer the purchase of NPA portfolios. Starting with an MNC bank, it bought many portfolios from private and public banks, and along the way, the SARFAESI Act, of 2002 catalyzed business momentum. Kotak’s bold conviction, driven by its uncanny long-term vision, resulted in big business, generating high IRRs, commensurate with the risks taken. Kotak, at that time an NBFC, focused on strong capital reserves and prudent risk management. Once safe, it applied to the RBI for a banking license and began a new phase of growth in 2003.

As the credit crunch post, the collapse of Lehman Brothers went global in 2008. Sectors such as power and infrastructure were badly hit, and overall economic growth was plummeting. With the entire banking sector paralyzed by bad loans, Kotak had a field day. The bank’s bad loans, including stressed assets, stood at 2.39% in crisis-ridden FY09 but were down to 1.73% by FY10. Its advances grew 25% to 20,800 crores that year, and the bank clocked its then highest consolidated profit of Rs.1,300 crores.

Until FY09, KMB’s loan book primarily comprised retail loans (auto loans, CV loans, personal loans, home loans, etc.) with the share of retail loans being as high as 89% in FY08. However, the bank’s loan mix altered significantly post the financial crisis as the bank increased its focus on the corporate segment and cut down its exposure to the high-risk personal loan segment. Corporate loan book growth outpaced overall loan book growth in the coming few years, as KMB capitalized on its relatively well-capitalized balance sheet and superior asset quality to lend to blue-chip corporates during the 2008-09 financial crisis. While the bank’s overall advances grew by 2% in FY09, the corporate loan book growth was 20%. Similarly, overall advances grew 32% in FY10, while the corporate book doubled during that year. As other lenders became risk wary or faced the heat of the financial crisis, it gave KMB the opening it was looking for to enter the balance sheets of large Indian corporates. By the end of FY10, a quarter of KMB’s loan book comprised corporate loans vs. 11% in FY08, making it a much more stable bank with a balanced loan book mix.

It pays to act with alacrity in a crisis. "Run your business knowing it might be sunny, it might be stormy, or in fact, it might be a hurricane,” Jamie Dimon once said. “And be honest about how bad a hurricane might be." When a crisis strikes, it’s best to prepare for the worst.

And that’s exactly what Kotak did when the Covid crisis hit. It was the first bank to do a QIP despite its share price being down 30% to build a fortress balance sheet.

Only the strongest boats will see through the storm. A fortress balance sheet is a must, and this was one of the objectives of the bank’s QIP issue of 7,400 crore in May 2020. I am happy to report that the QIP had an overwhelming response. The Bank’s Tier-1 capital adequacy ratio (CAR) which was about 17% as on 31st March, 2020 has gone up to over 20% post issue. This additional capital will support the bank in dealing with contingencies or financing business opportunities (organic and / or inorganic).

— Uday Kotak

Taking risks is an inherent part of the business, but managing risk takes considered judgment, which Uday Kotak has.

A bank’s profits are derived from its balance sheet.

Over the years, I have found banks focusing more on the P&L than on the Balance Sheet. In fact, particularly for banks, the Balance Sheet is more important, and P&L is only a derivative of the Balance Sheet.

— Uday Kotak

For banks, while a profit is certainly important (who doesn’t want to make money?) it all begins and ends with the balance sheet. A bank’s profits are derived from its balance sheet. A bank with a bad balance sheet will have poor results and won’t be able to earn enough to survive a financial crisis. Even if survival isn’t at issue, a bad balance sheet will virtually ensure that a bank can’t earn its cost of capital.

Think of a bank as a machine, a continuous machine that takes in deposits, makes loans with those funds, and receives interest and ultimately the return of principal on those loans. The balance sheet is a snapshot of this machine frozen in place. It reflects the bank’s financial position at a single point in time.

We have seen that Kotak has its liability engine in place and more than enough capital adequacy to fuel the assets' engine going forward.

Because the majority of a bank’s income statement is derived from their balance sheet there aren’t many things to investigate that we haven’t looked at otherwise. The largest items on the income statement we haven’t seen at this point are non-interest expenses and non-interest income.

In a typical case, the majority of non-interest expenses for a bank are their operating costs. Operating expenses are a large category. Operating expenses consist of anything and everything related to operating the business from employee salaries, rent, marketing, and information technology costs down to the purchase of branded pens, and tiny calendars.

Kotak’s operating expenditure stands at 11,121 crores as of 31st March 2022. This translates to Opex-to-Net Interest Income of 66% which is fairly high as compared to peers.

Efficiency is more about revenue than expenses. Highly efficient banks aren’t necessarily those with the lowest costs. The typical bank earns twice as much revenue as it pays out in expenses. Uday Kotak believes that cost-to-income is an outcome rather than a target.

Ultimately cost to income will get corrected, but we are very clear at this stage. There are three clear engines which we are growing. First is on retail loans and there are front end acquisition costs. Just think about home loan. If there is a fee for acquisition or distribution to be paid a home loan, which has say average life of six, seven years or eight years though the loan may be 15 years average life is six, seven, eight years, you’re paying the fee cost upfront. And under banking regulation you have to take the full distribution hit at the point of time you underwrite the loan. And that doesn’t bother us because we are driven by underlying value creation, not necessarily what it does to my pre operating profit in a quarter that is not something which is the basis on which we take decisions, if we believe substantively it is going to add value, we are ready to take those costs upfront. But that is one, second you got to keep in mind, we have dramatically increased our customer acquisition from eight lakhs in the last year same quarter to 21 lakhs in this quarter. And we see that engine continuing to fire, again that takes front end cost. And we of course are very focused on unit economics of our acquisition cost on customers. But we think the acquisition cost upfront is not something which is going to deter us as long as we believe the underlying unit economics are strong. Therefore that is point number two. And point number three is, with the opportunity in the marketplace, which is coming in, with our overall balance sheet metrics, we will drive growth and we believe the cost to income ratio will be an outcome rather than a target. Therefore we think about getting the right outcomes, which will improve the cost to income ratio, because a lot of our costs are front end. And also keep in mind that as we get more and more digitized, the actual straight through processing digital lending transactions will ultimately reduce the effective intermediation cost as well. But these three or four parameters are what is going to drive us and in simple language first is really, the front end cost we are ready to take. Second, if we are growing our customer base at a very high speed, keeping in mind unit economics versus front end cost. Digitization will ultimately make straight through journeys, significantly lower operating costs, and fourth cost to income for us is an outcome, not a target.

A bank's non-interest income line item on the income statement encompasses any additional income the bank generates outside of interest from its lending activities (which also includes dividends received on its investment securities book). This could be anything from overdraft fees, fees for investment management services, mortgage servicing fees, credit card lending fees, and any gains (or losses) from sales of securities. Kotak’s other income stands at 6,354 crores as of 31st March 2022.

Metamorphosis Into A Concentrated India — Diversified Financial Services Powerhouse

Fortunes can be made in banking, but only by earning consistent returns through multiple cycles. Banking isn’t a get-rich-quick business. There are graveyards full of banks that chased short-term performance at the expense of long-term solvency.

As many who have tried and miserably failed have realized, financial services businesses cannot be built in a few years or even a decade. Uday Kotak’s entrepreneurial journey from the founding of Kotak Mahindra Financial Ltd. (KMFL) in his family’s 300 square foot office to recently claiming the spot for the richest self-made banker in the world has been a journey of 35 years.

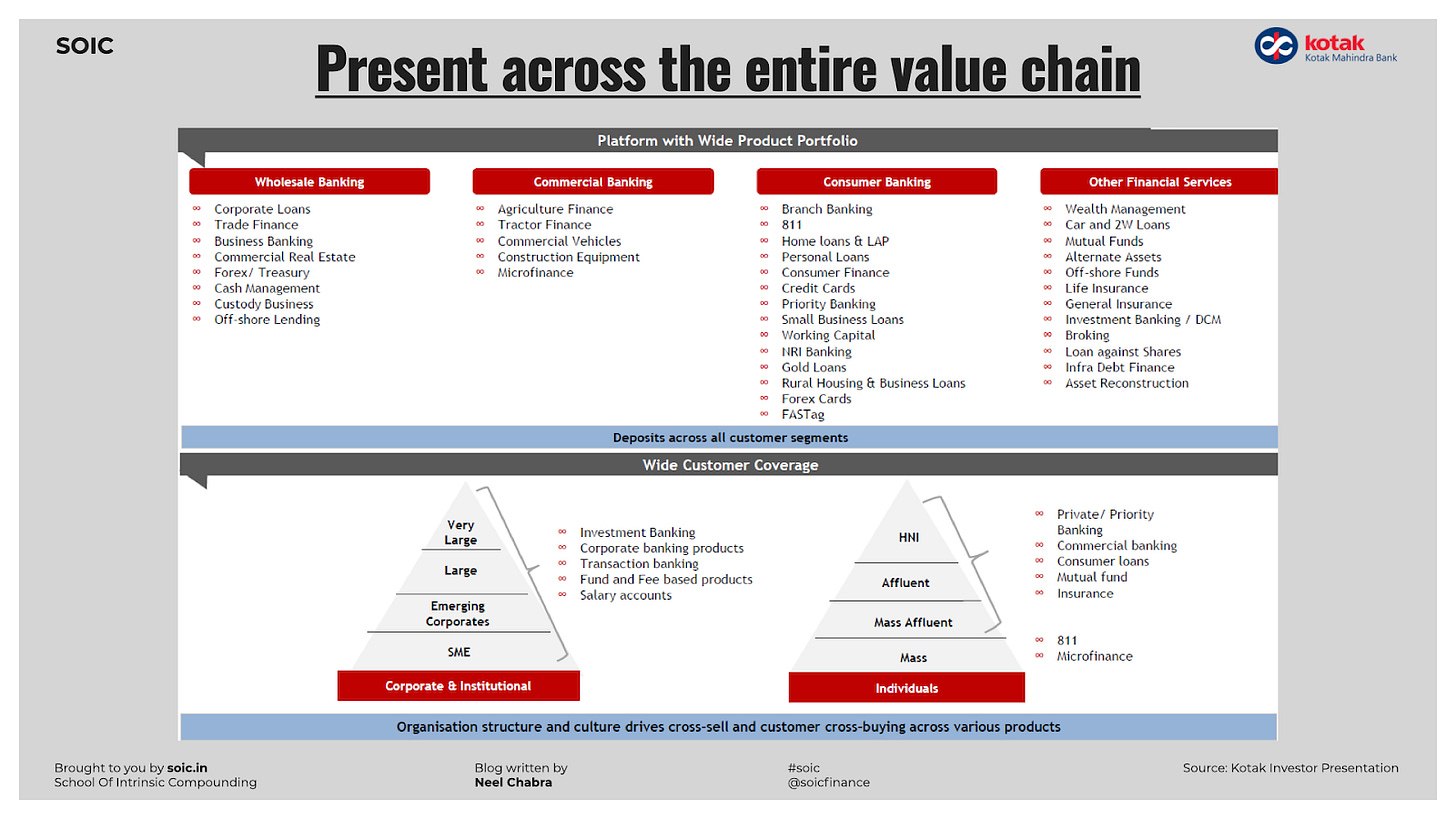

Over the last 35 years, Kotak has built up its business to provide the full suite of financial products for its customers.

It commenced operations in 1985 as a non-bank finance company providing bill-discounting services. In 1987, they entered the lease and hire-purchase business. With the opening up of the Indian economy in early 1990, they entered the auto finance (1990) and investment banking (1991) business to capitalize on new opportunities. Kotak completed its initial public offering (IPO) in 1992.

In 1995, Kotak entered into a joint venture with Goldman Sachs and incorporated Kotak Mahindra Capital Company, its investment banking subsidiary. In 1996, the auto finance business was hived off into a separate company - Kotak Mahindra Primus Limited (now known as Kotak Mahindra Prime Limited), a joint venture with Ford Credit to finance non-Ford vehicles. Kotak also took a significant stake in Ford Credit Kotak Mahindra Limited for financing Ford vehicles. In 1998, they began the asset management business with the launch of India's first gilt fund managed by Kotak Mahindra Asset Management Company. The life insurance subsidiary, Kotak Mahindra Old Mutual Life Insurance Limited (now known as Kotak Mahindra Life Insurance Company Limited) was incorporated in 2000 as a joint venture with Old Mutual Plc. Kotak Life obtained a license from the IRDAI dated January 10, 2001, for carrying on the business of life insurance and annuity. Subsequently, after the corporatization of individual brokers was permitted, the stockbroking business became its subsidiary, Kotak Securities. In 2003, Kotak Mahindra Finance Limited ("KMFL"), the Group's flagship company, received a banking license from the RBI. With this, KMFL became the first NBFC in India to be converted into a commercial bank - Kotak Mahindra Bank Limited.

In 2004, Kotak became one of the early entrants into the alternate assets business with the launch of a private equity fund. Thereafter, they launched a real estate fund in 2005. In 2005, Kotak realigned its joint venture with Ford Credit to take 100% ownership of Kotak Mahindra Prime (formerly known as Kotak Mahindra Primus Limited). It also sold its stake in Ford Credit Kotak Mahindra to Ford Credit. In 2006, Uday Kotak took a stunning contrarian stance. While prominent investment bankers sold their business to foreign partners, rattled by the might of global players and the changing complexion of India’s corporate sector in favor of global companies, Kotak decided to do exactly the opposite — buy out the stake from foreign partner Goldman Sachs rather than selling out.

In 2008, Phoenix Asset Reconstruction Company, sponsored by Kotak Mahindra Group, obtained registration from RBI to conduct the business of securitization and asset reconstruction. In 2008, Kotak also opened Kotak Bank's representative office in Dubai. In 2009, they launched Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Limited, which is appointed as a pension fund manager by the PFRDA for managing funds under India's National Pension System. In 2015, Kotak received IRDAI approval to commence our general insurance business through Kotak Mahindra General Insurance Limited. In 2017, Kotak bought out the remaining 26% equity stake held by Old Mutual Plc in Kotak Life to make it a wholly-owned subsidiary. Kotak Infrastructure Debt Fund Limited was converted into a company focused on infrastructure debt financing business after approval from RBI. The regulatory approval for registration as a non-banking financial company from RBI was received on April 6, 2017. The company is engaged in providing finance for infrastructure projects. Kotak has pursued growth through inorganic initiatives as well. In 2015, IVBL merged with the Bank, which is one of the largest private sector bank mergers in the Indian banking industry. In 2017, Kotak acquired BSS Microfinance Limited, which is in the business of microfinance. Further, it started its international banking unit in GIFT City in 2016 and opened its first international branch at DIFC in 2019.

Building on its strategy of Concentrated India — Diversified Financial Services, Kotak has become one of India’s leading diversified and integrated financial services conglomerates, providing a wide span of solutions across banking (consumer, commercial, corporate), credit and financing, asset management, life and general insurance, stockbroking, investment banking, wealth management, microfinance, and asset reconstruction, encompassing all customer and geographic segments within India.

The group is a megalith today, comprising 18 subsidiaries under KMB, which are 100% owned by the bank.

The Whole Is Greater Than The Sum Of Its Parts

Kotak’s diversified and integrated model gives Kotak the ability to take advantage of shifting economic environments. Kotak has balance-sheet driven businesses, such as lending and investing, to capitalize on favorable interest rate movements, market-driven businesses such as stockbroking, mutual funds to capitalize on favorable capital markets conditions, and knowledge-driven businesses such as investment banking and investment advisory to maximize fee-based income, deepen relationships and increase customer penetration.

The diversified nature of the business leads to significant cross-selling opportunities, enabling it to garner a larger proportion of potential revenue from its customers to meet their diverse financial requirements. For example, Kotak is able to realize advisory fees by providing investment banking services, underwriting fees by arranging bond financing for a transaction, and service income by acting as the escrow bank for a transaction, all while deepening its customer interactions and relationships, which they can then leverage into corporate banking services.

The bank’s integrated approach is the best model, as a stable annuity business balances the ups and downs in the capital markets linked businesses. With multiple engines in place—different engines fires at different times, and this give the company a sustainable and resilient business model.

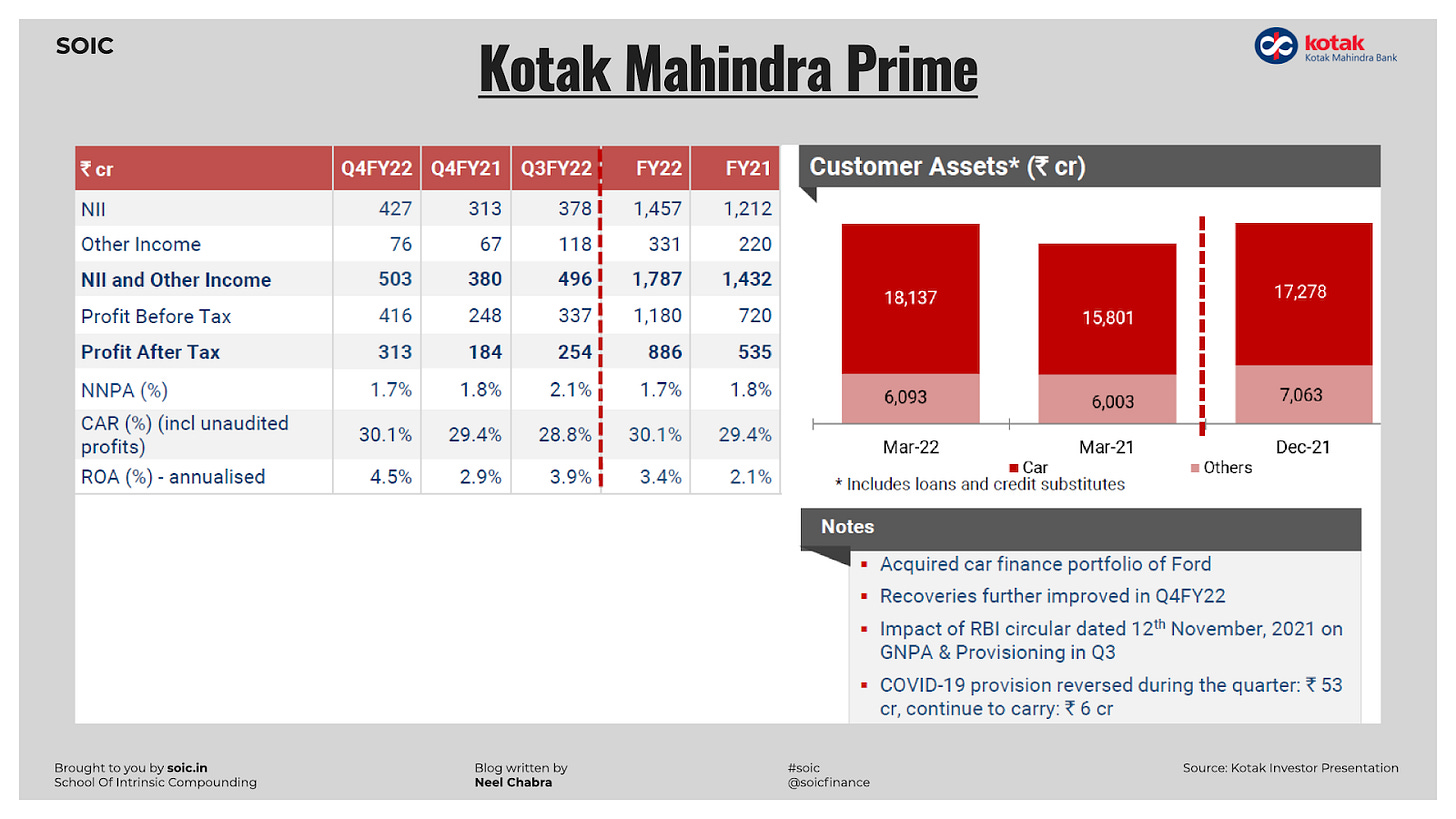

Kotak’s banking operations brought in 70% (8,573 crores) of the group’s total profit of 12,089 crores as of March 2022. In addition to the bank, Kotak has two wholly-owned subsidiary NBFCs that do lending — Kotak Mahindra Prime which brought in 886 crores (7%), and Kotak Mahindra Investments brought in 371 crores (3%). The asset quality of both the NBFC is top-notch, with NNPAs of 1.7% for prime and 0.6% for investments. Why does it lend through NBFC instead of the parent bank? Keeping them separate allows them to focus on a specific niche. Also, NBFC has the advantage of not having to set aside capital for CRR-and-SLR. Plus, it is not forced to do priority sector lending.

Kotak Prime is primarily into car financing which includes financing retail customers of passenger cars, and multi-utility vehicles, and term funding to car dealers. Around 75% of advances go towards car loans, and the balance is for the loan against securities, corporate loans, and developer financing.

Kotak Investments is primarily engaged in finance against securities, lending to real estate, and other activities such as holding long-term strategic investments. It also does structured finance for corporate clients and acts as a solution provider.

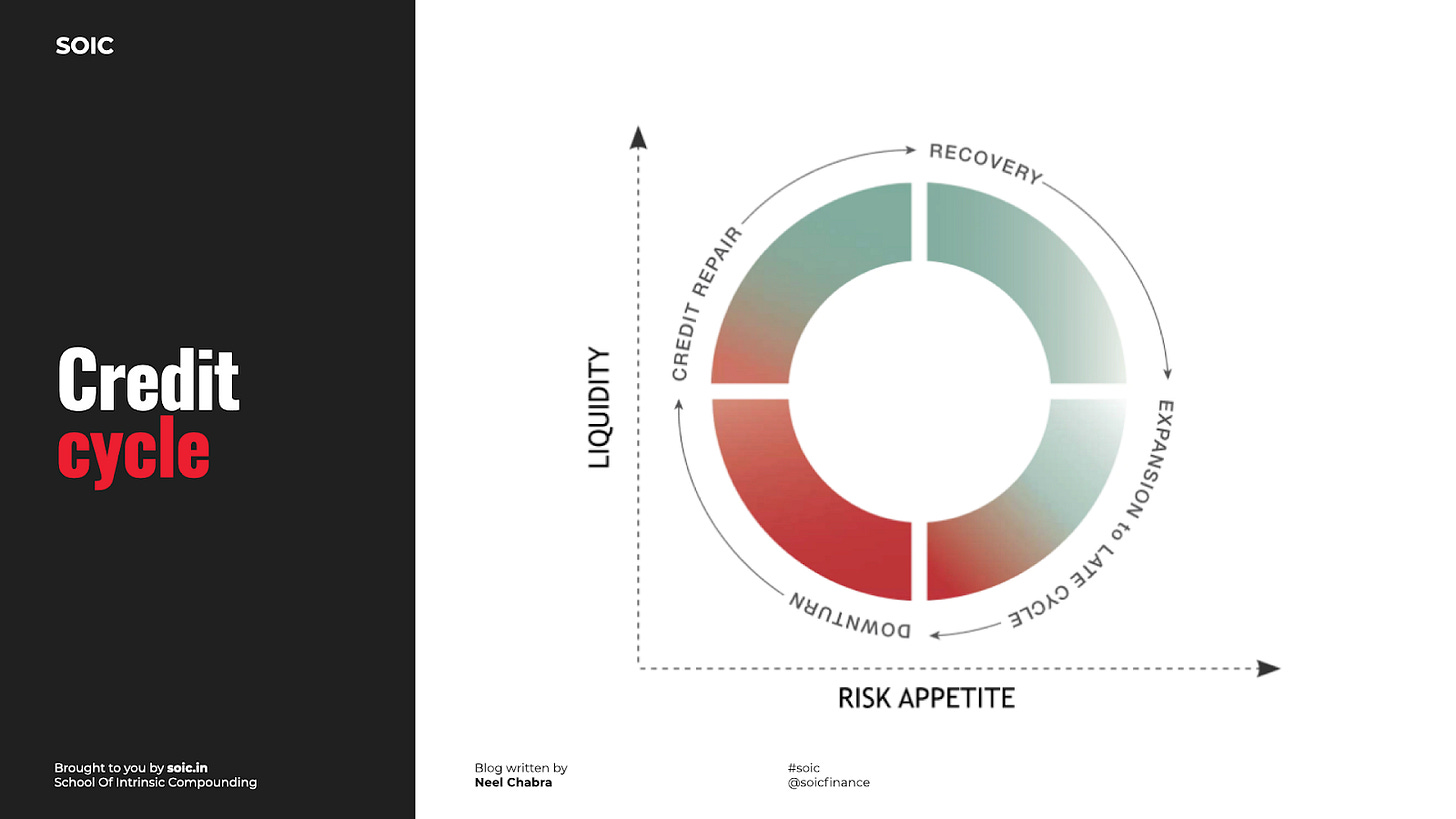

All in all Kotak’s lending operations brings 80% of the group’s profit. Lending goes through a credit cycle. A credit cycle usually mimics the economy, and there are 4 phases to it.

The first phase is the expansion phase, where relatively easy lending standards are followed. We see increased borrowings in the market.

Then slowly as this happens, there is the downturn phase where companies begin struggling to meet their financial obligations due to stalled or negative growth. Banks start being more careful about who they lend to. So cheap capital is available only to tier-one institutions.

Slowly and steadily, then the repair phase comes whereas liquidity diminishes, companies start to fail and default rates rise. This leads to the government being more concerned about having to repair the balance sheets of banks, especially public sector banks, while banks want to reduce costs and clean up their balance sheets.

We also see more asset sales, and then there is the recovery phase where the margins begin to improve, and credit becomes better. Companies start to grow. Then, once that finishes, we again enter the expansion phase.

While we are in the fourth phase of the credit cycle right now, we should not forget that lending is inherently cyclical. Though the demand for credit will far outstrip supply in the coming decades in India, this does not change the fact that we will have these credit cycles playing out in between. Moreover, lending as we know is a fragile business. There will be times when Kotak will take a cautious approach to lending, but its other non-credit risk franchise businesses — the brokerage, mutual fund, investment bank, wealth management, and insurance will thrive. These are relatively low-risk businesses and have provided the Group with a stable, growing source of revenue.

Kotak Mahindra Life Insurance Company Limited (KLI), a 100% subsidiary of Kotak Bank, is in the business of Life Insurance, and annuity, and provides employee benefit products to its individual and group clientele. KLI has developed a multichannel distribution network to cater to its customers and markets through the agency, alternate group, and online channels on a pan-India basis.

Life insurance is a push product sold through agents. It is an emotional product, and brand recall is essential for selling life insurance. A bank is at the center of a person’s financial needs. This is the reason why insurance companies have chosen banks as a distribution channel. The trade name for this channel is bancassurance. Kotak sells 51% of insurance through this channel, which is in line with other private players’ shares from the bancassurance channel.

Kotak is well-balanced — having equal sales of the group and equal sales of individual products. On the individual side, the products sold through agencies is 50 percent and the rest 50 percent by non-agency that as Banca and others.

The insurer is expanding its distribution footprint and adding more branches. In the calendar year 2022, they expect about 30 percent growth in its distribution footprints. The insurer also plans to invest in data analytics and technology interfaces. It will be adding more partners on the agency side and bancassurance. It is also looking at a direct-to-customer digital play.

The embedded value of the life insurance business in FY22 is 10,679 crores, against 9,869 crores a year ago. The value of the new business for FY22 is 895 crores, against 691 crores in FY21; the bank’s VNB margin is at 31.1% which is among the best in the industry.

Gross written premium in FY 22 grew 17.3% to 13,015 crores, against 11,100 crores a year ago. The operating expenses ratio improved to 12.8% in FY22 as compared to 13.6% in FY21.

Kotak Securities is a leading secondary market broking firm offering services to retail and institutional investors. It provides broking services in equity cash and derivatives segments, commodity derivatives, currency derivatives, depository, and primary market distribution services. It has a full-fledged research division engaged in macroeconomic studies, industry, and company-specific equity research. The securities business is prone to capital market cycles. It gets beneficial when the capital market is in a positive mood. Operating leverage kicks in with scale, and the top line directly flows to profits.

Kotak Securities brought in 1,001 crores in profits in FY22, against 793 crores in FY21.

There are two segments that you can trade in the stock markets in India. One is the futures-and-options segment and the other is the cash segment. Kotak Securities focuses on the cash segment for retail investors. Margins in the cash segment are higher than in the future-and-options segment. Over the years, industry structure changed, with traders becoming a more significant part of the market with futures and options. So, while Kotak has been losing market share of the overall securities market, it has increased its market share (cash) from 9.3% in FY21 to 10.6% in FY22.

Kotak Mahindra Capital is a leading, full-service investment bank in India offering integrated solutions encompassing financial advisory services and financing solutions. The services include Equity Capital Market issuance, M&A Advisory, and Private Equity Advisory. In FY22, it brought in 245 crores, against 82 crores a year earlier. Though a small proportion now, it was once responsible for bringing in over 50% of the group’s profits (pre-2008). It ranks #1 in IPOs of over 1,000 crores, having led 8 out of 10 of such IPOs. And have a 64% market share across all Equity Capital Market (ECM) transactions.

Kotak Mahindra Asset Management brought in 454 crores in FY22, against 346 crores a year earlier. The AMC Industry has low entry barriers but massive barriers to scale. Kotak has scaled this business well and is consistently gaining market share both in terms of overall AUM and Equity AUM.

In addition to Kotak’s lending operations, the non-lending operations hold immense potential to be scaled up even further over the next decade, which requires relatively less capital. The group’s foray into General Insurance in 2015 also looks promising, along with its wealth management, pension fund, and alternate assets business.

Worth The Buck?

The problems with valuing financial service firms stem from two key characteristics. The first is that the cash flows to a financial service firm cannot be easily estimated, since items like capital expenditures, working capital, and debt are not clearly defined. The second is that most financial service firms operate under a regulatory framework that governs how they are capitalized, where they invest, and how fast they can grow. Changes in the regulatory environment can create large shifts in value.

— Aswath Damodaran

As I write this, Kotak has a market cap of a little less than 3,50,000 crores — With a net worth of 97,000 crores, a loan book of 3,00,000 crores, and total assets at 4,30,000 crores. It brought in profits of over 12,000 crores in FY22, with an ROA of around 3%, which is the best in the industry—partially because it operates with lower leverage. And despite low leverage, it has ROE of over 16% while having the highest capital adequacy of 24%.

Kotak’s concentrated India — diversified financial services business model is a surrogate for the booming Indian economy, and Uday Kotak believes that Kotak will grow 1.5-2x India’s Nominal GDP.

I don’t know at what P/B or P/E multiple Kotak should trade at, but I know that Kotak will be far more valuable in ten years than it is today. And I know this through osmosis. This view is in light of the facts available to me right now, I will change my mind, when the facts change, what will you do, Sir?

Thank you for reading, see you soon!

Lovely essay